The Room

I hate that I have to lie. I hate the word lie. I hate lies. But I live one. I live the lie that lies about the person I love and the lie about being what I am. I live the lie that lets me believe I’ll ever have everything I want from him. I never wanted to think that’s what I am, a person who lives a lie. But I don’t know, I don’t know.

I am in love with a guy. I am a guy. This is fucked up on more levels than I can think about. What’s even more fucked up is that we’re fifteen now and I’ve been in love with him since we were six. How can you be in love with someone when you’re six?

I live in this neighborhood called

Jerome was in my first grade class. That’s where we met. He was the smartest kid in the class and the best artist. I was the dumbest and the worst artist. I hit him every chance I got. And since my drunk-ass dad forgot to sign me up for school I started a year late and I was almost a year older than him so I was bigger. I only got in trouble for it when another kid saw me doing it and I only got in trouble at school; my dad even then was a drunk and my mom left him when I was two to go fuck his brother three states away. We don’t even have a picture of her in the house. She cranked out seven boys and then took off, just like that. I guess I was the last straw. I don’t know what she would have done with me when I was six and got busted for beating up another kid. My dad didn’t do shit. He didn’t give a shit, and he still doesn’t give a shit, and I don’t care. Fuck him. I got in trouble at school and had to stay in at recess and write sentences because I thought Jerome was the nicest person I’d ever met and also the prettiest and he had to suffer for that because I wanted to be that and it was never going to happen.

I picked on him and beat him up for four more years. Some years he was in my class, some years he was in another class. But I always saw him at recess. He never cried. He never tried to fight back. This one time I punched him in the stomach. I felt my hand go into his stomach and it was soft at first then hard. He sort of fell backwards and put his hand over his stomach all hunched over. I hated myself and I wished I could feel the pain my fist put in his stomach when I hit him instead of him feeling it. I wished he would fight back and hit me or scream and run or do something but he just didn’t and it made me crazy. I thought about him all the time and thought about the things we could do together like skateboarding and he could teach me to draw and I wished he was with me when I was at home and then when I saw him I’d hurt him. It was a demon making me do it. It was a demon that thought fucking someone up meant you hated them so I tried to fuck him up so it would make me hate him but I just loved him more and more and more. And the more I loved him the more I wanted to hate him and the more I tried to fuck him up.

In fifth grade we were in the same class again. At recess one day I snuck up behind him and hit him on the back of the head and said “Faggot, what are you doing drawing, that’s for sissies.” It’s like I was watching myself by then. I just wanted to see him turn his head so I could look at his face. He was drawing a picture of kids playing soccer and it was all just right, you could tell what everything was and even which kid was who in the picture, kids from our class. And when I hit him it made the pencil dig into his paper and draw a line in a wrong place. He put the pencil down and he looked at me and I knew he was finally finally after my whole life of fucking him up going to do something about it. I felt this big shit-eating grin come onto my face and I didn’t even bother trying to move out of the way when he stared right at me and balled his fist up and punched me in the throat.

I didn’t expect it in the throat. I wanted it in the face. I wanted him to break my face for all the shit I’d done to him that he didn’t deserve. I wanted him to blind me with the fury of his fist buried right in my eye socket. But he aimed low. He did it on purpose too, and I realized it as soon as he’d done it because his face had this look on it like he knew it wasn’t a mistake to hit me in the throat. I couldn’t breathe. It shocked me. I grabbed my throat because it was like something had stuck in it and wasn’t letting air in and out. I started to panic and I tried to scream but nothing happened because I couldn’t get any air.

And he wasn’t done. He stood up and picked up the chair he’d been sitting in and he hurled it through the air at me and hit me in the side and knocked me over. I had no more room in my head to be shocked because I couldn’t breathe. I couldn’t think about anything else. I fell under the force of his hit and lay there on the classroom carpet trying to get some air and half-trying to fend off the blows. He kept hitting me over and over with the chair. I rolled onto my side and finally started getting some air and held my arms up to stop the chair from hitting my face even though I could breathe again and I was smiling liking every hit because I deserved them all, and I heard girls in the class screaming and I saw Jerome’s eyes while he held the chair over me. I saw that he wasn’t angry. He was looking at me like he was trying to figure out what I’d do. Like he was studying me and he was going to write down what I’d do like I was some experiment. The teacher yanked him away as he held the chair up ready to smash it down on me. I lay there getting air back into me and they took him away. The nurse came and asked me a million questions and I didn’t answer any of them, I just smiled and smiled and smiled some more because I was such a mean son of a stupid bitch and he might have put a few dents in me but he hadn’t broken anything and I was so glad this had happened because now I could stop beating him up and get on with things, whatever they might be.

They turned out to be, we became best friends. All the things I pictured in my head us doing together, we started doing them. He lived on the other side of the state route, in the nicer neighborhood. It wasn’t like the rich neighborhood down the route but it was sure as shit better than my neighborhood. None of the kids from his neighborhood came into mine, but kids from mine went into his. That was normal. Jerome wasn’t normal and he came into my neighborhood. He came to my house and I got my skateboard and my brother’s skateboard and I taught him how to do it. We skated all over my neighborhood. We went to the woods at the back of the neighborhood and poked the condoms and coke cans and trash in the creek with sticks. We built a thing back there, I didn’t want to call it a fort because that sounded gay but I guess it was a fort, we built it out of tree branches and some milk crates we found and old blankets and some shit my brothers stole from the lumberyard and never used. We built this little room and we would sit in it and not talk. He had scraped the ground clean inside there and he would draw in the dirt with his fingers. And we would play games of hangman and tic tac toe and I’d draw dirty pictures in the dirt. He never did and when I did it he’d leave the room we built. We also built fires inside the room but small because if they were big they’d burn through the roof. Jerome sometimes would burn himself in the fire on purpose. I got all cracked inside when he did that and I told him to stop that shit or I would hit him but he would just look at me with his wrist over the flame and I couldn’t hit him and after a minute he’d drop his eyes and look down at the fire and lay his hands in his lap and we would stay quiet again. I would look at the big scar on his arm where he cut it open with glass when he was ten. It must have been before he hit me with the chair because he had it then I remembered. But I didn’t know what it was from.

We stayed best friends in sixth and seventh and eighth and ninth grades. I learned him. I learned about his swim team thing and his cutting thing and that he could drink a lot but not as much as me because my brothers started giving me liquor when I was six and I could handle it better than Jerome who got sick a lot. I learned his dad was an asshole and Jerome hated to be at home. I learned when I was making out with Karl’s twin sister Mandy down the street sometimes it turned into Jerome’s tongue in my mouth and that was super fucked up at first and then it was hot and I closed my eyes and pretended it was him I was kissing and things got all fucked up in my head and Mandy was like what the hell are you doing. I wanted to hurt him again. This could not be happening. Bad things started happening when we changed in the same room to go to bed when he stayed over. I never stayed at his house. He stayed at mine always. My craphole house and my craphole room I shared with two of my brothers who were hardly ever home. I always had to turn away and not look at him change because seeing him naked got me hard and that freaked me big time. All the thoughts I had when I was a kid about him and all the feelings I had were flat like a drawing and then suddenly they were not flat, they were real life and moving around and talking and filling up my head and my whole body when I was around him and threatening to spill out. Maybe he knew. I don’t know.

And then he got sick. He got really sick. In eighth grade one day he started looking not right but I didn’t say anything. I thought he was just going to get the flu. He got strep throat and then he didn’t get better. Like he started to get better at first and he came back to school one day and we had our trays in the cafeteria going to a table and then fucking wham he was on the floor and his food spilled all over and all these girls came over and surrounded him and he looked dead as a doornail and I couldn’t do anything and I just wanted to die because at that second I knew sure as shit I was in love with him. I was in love with a guy and for five seconds that didn’t even matter because I wanted to save him and cure him and make it so he wasn’t passed out looking dead on the floor of the cafeteria surrounded by girls freaking out and now teachers and the janitor and then he woke back up some and looked around like he was terrified. His eyes moved all over and came onto me and he looked less scared. The school nurse came then and she told everyone to clear out of the way and she backed us all off and helped him sit up. She sent someone else to get him a wheelchair and he looked confused. I couldn’t stop looking at his face. He looked like he didn’t know where he was. His face looked strange. It was pasty white in some places and red in other places. He was so beautiful I felt sick looking at him and Karl punched my back and said what a sissy freak fainting like a girl and I turned around and I said fuck you Karl and I left the cafeteria and I went into the bathroom in a stall and held my head for a long time in there and maybe I cried a little and then I cut out of school because if Jerome wasn’t in school then I sure as shit had no reason to be there.

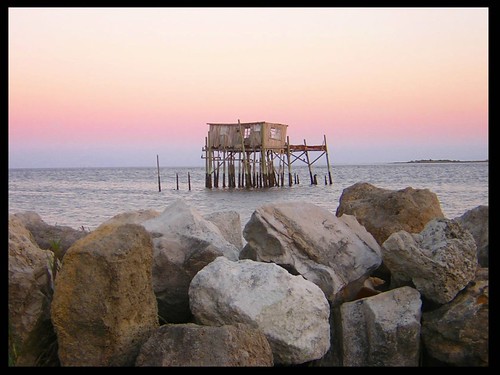

I didn’t go home. I went to our room we made. There was still this picture on the floor he’d left, these lines in the dirt. It was this circle pattern. I traced over it and I thought about him and I stayed there and I slept there. I woke up in the middle of the night and it was cold even though it was still September. I went home and got a coat and I started walking to his neighborhood. I walked across the route and into his neighborhood and to his house. His window was on the first floor and I started knocking on it. I looked in there and he wasn’t in there. There was a light on in another room and I snuck around and listened outside the window but all I could hear was the TV. I looked in and saw his mom and his sister asleep on the couch in a ball with their heads on the armrests. I don’t know why but that scared me and I ran all the way home but when I got there I couldn’t go in because two of my brothers were playing poker with some guys in the kitchen and they’d tell me to play too and I couldn’t just then. I went back to our room we made. It was still cold. I traced the pattern in the dirt again and then I wrote I love you in the dirt and then I spit in it and smeared the mud it made on my hands.

I was late for school the next day and the only reason I went was to find out what was wrong with him. I asked around, I asked all those preppy girls that came to him when he fell. No one knew. He wasn’t at school. They didn’t want to talk to me anyway, I was the stupid mean

That started the bad time. It lasted so long, like as long as my whole life had been, I lived it all again in that short time that stretched like retching when you’re drunk. Jerome didn’t come out of the hospital for a month and a half and when he did come out he was bald and his face was swollen and he hardly looked like the one I remembered and loved. He had leukemia. He had his birthday in the hospital, he turned fourteen. I was almost fifteen and I felt rage that somebody could get sick like that when they were just fourteen, like you’re supposed to be healthy when you’re fourteen, not laying in a stupid bed because you’re too fucking sick to even get out of it. Jerome couldn’t come over any more. He couldn’t go to school. He just stayed at home in bed getting better from chemo so he could go back and do more chemo and get sicker. I felt like I was feeling everything he felt in my body. I went to see him every day after school. His mom was there sometimes but sometimes not. His dad was never there. His sister was there some days too when she wasn’t working at her after-school job. We didn’t do anything except sit in his room with the door shut and everything quiet. He asked about people at school and I told him everything that was going on that I paid attention to except sometimes I had to make things up because the real truth was that I spent all day thinking about him and when I could get to his house and spend that quiet hour and a half in his dark bedroom being near him and it made it a little hard to pay attention to who was going out with who and who kicked whose ass in the McDonald’s parking lot last week and how many times Karl said he scored that week. Jerome didn’t care anyway. He just seemed glad to see me and I think I could’ve talked about the different kinds of grass growing in the yard and he would have been glad just to have someone in there talking to him and listening to him. He didn’t talk much because he was so tired all the time. I saw the lines on his arms and I knew he was cutting but we didn’t talk about it. He hid his arms under the blanket whenever his mom came in.

It got colder and he went back to the hospital. He went back for more chemo because he said it didn’t kill all the leukemia the first time. He had to have radiation too. He’d call me sometimes late at night, it didn’t matter when the phone rang at my house, someone was always up to get it. He’d call me when he couldn’t sleep and I’d take the phone in my room and talk to him and tell him stupid shit about school and about all the crap I was doing to our room in the woods. I’d been trying to fix it up and make it sturdier and I’d gotten all these blankets I folded up and put around the walls and even a bunch of shingles that I tried to nail to the top of the roof but it didn’t work because the roof was like this chunk of plywood that was warped, and the nails made it split, and I told him all about it and about new shit I was figuring out how to do on my skateboard. Sometimes I could hear nurses coming in his room and sometimes I could hear him getting sick and then catching his breath and asking me some question to make me keep talking. I guess he just wanted something to think about other than where he was. I couldn’t think about anything else but where he was.

He came home again and I thought he was going to die. He looked like he’d died and someone put just enough electricity in him to make him able to move. Like he was a corpse with some fucked-up current going through him, making him move barely enough that you could tell he wasn’t dead. His skin had turned this flat gray color except where it was red and he was always throwing up and he shook all the time even when he was covered in all the blankets and had a heating pad. His mom didn’t go to work while he was home that second time, so I could only stay like half an hour each day because she was always coming in and out of his room asking him if he needed anything and taking away the trash can he threw up in and bringing him more blankets and taking his temperature and cleaning out the thing stuck in his chest that they left in there, the thing they put the chemo chemicals in. I thought I was dying too. I went home every day after I saw him and I went to our room in the woods and I screamed. I don’t even think I screamed any words, I just hunched in a ball and screamed into my knees. My voice got all fucked up. I hated it. I was so pissed about all of it and about not being able to change it and the anger inside me just kept going deeper and deeper and turning into rot. The whole inside of my body was turning rotten and fuzzy and brown like rotten fruit. I imagined us as two whole people, two complete people and Jerome’s insides were like the inside of a peach, firm and peach and sweet and healthy. And I wanted to bite his peach body and eat it and swallow it and carry him inside me all the time because inside me he would be safe. Nobody could fuck him up inside me. When I went home and laid on my mattress in the dark I dreamed I was eating his body out of his bed and the chunks of his body when I pulled them off him turned into sweet peach in my mouth and I woke up and had to throw up. I started dreaming that dream almost every night.

I didn’t talk to anybody at school any more. My voice was all fucked up from all the screaming anyway. Karl was more of an asshole every day. I tried hard to hide it that I was dying of rotten inside my body because the person I loved was dying but I couldn’t hide it that I felt like shit all the time and I was tired and scared and just waiting for someone to tell me he was dead. Karl got meaner and meaner until one night we had this fight and I beat the crap out of him. I know he thought since I’d been moping around for two months and not skating as much and not drinking and not coming to their stupid parties in somebody’s shitty

Then Jerome went back to the hospital before he was supposed to. He was supposed to back on a Monday but he went back on the Thursday before. Nobody knew why. I was his only friend, those girls who clustered around him the day he passed out, they were just being stupid girls, they didn’t care about him. Nobody cared about him like I did because he’d always been the freak, he used to talk to himself in elementary school and he always got either and A plus or an F on his tests and nobody understood anything about him. I went to his house a couple times but no one was ever home. So the next week I cut class and went over to the high school and waited for his sister to come out to the parking lot and I talked to her. She had this glazed look on her face and she said he’d cut his wrists and now they had to tie him down to the bed at the hospital because every time he woke up he was trying to kill himself and he tried to drown himself in the toilet and then she like snapped her head up like she didn’t realize she’d been talking so much and looked at me and said why don’t you go see him, maybe you can talk some sense into him, what the hell happened to your eye. I said, your mom said I couldn’t. She said I’ll take you.

She took me. We didn’t talk on the drive there except she asked again about my eye and I said I got in a fight. I just sat in the passenger seat of her car holding my skateboard and swallowing because I was so fucking scared. Jesus I was scared. We got there and I got out of the car and I was still holding my board and she said leave that in the car and I was like oh right. She said you don’t have a cold or anything do you because if he catches it he could die. I followed her in and I stopped in the bathroom and scrubbed my hands and my arms and even my face and I stared at myself in the mirror at my black eye and I had to turn around and go in the stall and throw up because I was so scared that he wanted to die like that. When I flushed and came back out I scrubbed everything again and didn’t look in the mirror this time and went back out in the hall to meet his sister. We rode an elevator and walked down some more halls and there were these people everywhere who looked like hell, I guess they were in the hospital for a reason and I felt stupid and dirty in my punk skater clothes and my busted-ass flat-bottom skater shoes with the holes in the toes and I couldn’t look at anyone, I just followed her until we got to his room.

His mom was in there sitting next to his bed. I guess he was asleep. She looked at me and she looked at his sister like why did you bring him and his sister looked at Jerome and then the two of them went out in the hall and I was just in there with him.

I thought he was dead. He really was strapped to the bed. His wrists and ankles. He had all these tubes coming out everywhere and this mask thing on his face and there were all these machines and shit making little beeps and little whooshing noises and sighs and more quiet beeps. I couldn’t look at his face, I just looked at his arms and all the bandages covering them and the restraints over the bandages. The room got a little fuzzy and I remembered to breathe when he took in a breath. He opened his eyes and he looked at me. He looked right at me with his blue eyes that could see through whatever they looked at. He was looking right through me and I could feel him cutting all the layers of me open and then going straight out the back of my head and cutting through the wall behind me. Then he turned away from me and looked away from me and I could see nothing for a few minutes. I stood there holding onto the metal bed frame he was strapped to. When I could see again I looked down at his face turned away from me. There were tears coming out his eyes and rolling down the sides of his face. He didn’t act like he was crying but there were the tears. I turned around and saw his mother and his sister still out in the hall talking. I looked back at him. I reached my hand up and touched his face. I touched the water on his face. He closed his eyes and the places where his eyebrows used to be went down. I could hear a sound by his side and I realized it was his hand moving. I put my hand over top of his and he squeezed my fingers. His hand was so cold it was like touching a metal pole in winter. But I held it and held it and held it and stood there while he laid there and I watched him keep his eyes closed and felt the cold in his hand seeping up my arm and seeping into me. And I heard his mom and sister come back into the room and I let go of his hand and I started running. I ran out of the room and down the hall and hit the elevator button a thousand times until it came. I could hear his sister calling me but I couldn’t go back. The elevator opened and I got in and stood in there trying harder than I’d ever tried anything to hold myself still and as soon as the elevator opened I was running again, I ran through the halls to the exit and I ran out of the hospital and I ran until I had a stitch and thought I would throw up again and then I ran some more. I got lost and found the right road again and I ran all the way back to my neighborhood, it took hours, and then ran to our room in the woods. Because as long as I was running I wasn’t thinking that hard about him. I could only hold him in my head so hard while I ran. If I held still he’d fill me up.

I didn’t realize until I got to our room that my skateboard was still in his sister’s car. I started hitting things inside our room and breaking the walls and the ceiling and screaming and eventually I realized I’d destroyed our room. The roof had fallen on my head and my head was bleeding. I could hardly move everything hurt so bad. There were cuts on me from the nails that came through the roof when I tried to nail the shingles on. I turned around and left it and went home and got in bed. My brother Joe came in some time late. He saw all the blood on my pillow from my head and took me in the bathroom and cleaned it up for me and asked who in the hell had managed to kick my ass because he needed to shake the hand of the man who had bested me in a fight since no one had ever done it before. He didn’t know about the time Jerome beat the shit out of me in fifth grade. I told him nobody, I fell skateboarding. He said where the fuck’s your board, I didn’t trip over it coming in like I always do. I couldn’t even answer. My head was stinging like a son of a bitch where he’d poured peroxide on it and my ears were ringing. He said “stay here” and went out. I sat on the toilet sniffing and wiping my face off because I sure as fuck didn’t want him to see me crying when he came back. When he came back he gave me a bottle of rum and a couple white pills and told me to take them. I took them with the rum and went back to bed and in the morning I woke up thinking someone had strapped my head to a board it hurt so bad.

I quit going to school for a while. Christmas came. Like usual I didn’t get anything. I didn’t care. I was trying to carve this thing for Jerome, this little dog, out of this piece of wood I’d found but I fucked it up and accidentally cut the tail off. I threw it away and sat on my bed with the knife I’d been using and I looked at my arm and thought about all the lines on Jerome’s arms and his body where he cut himself. I put the knife on my arm and I was getting ready to cut it I wanted so much to know why Jerome did it and if this was what life was gonna be like for the rest of it then maybe I’d just go ahead and cut all the way through my arm and maybe my neck too and of course Joe came in right then and started yelling at me and took the knife away and hit me on the back of the head and told me I’d better not fucking do anything like that ever again.

More time passed. I went back to school for something to do because staying at home in bed was making me rot inside. I hadn’t talked to Jerome in all the time he’d been gone. He hadn’t called me late at night. I wondered a lot if he was dead. I went to the high school and waited for his sister sometimes but I always must have mistimed it because I never saw her. I went to his house at night and looked in the windows. Most nights I’d see Angie and his mom on the couch watching the TV with their faces glazed.

One night I decided it was the last time I was gonna go look in their window, it was spring and starting to get warm outside and I knew I was just fucking myself up thinking about Jerome all the time and wondering if he was alive and so I went expecting to see no one or his mother and sister and I went and I looked in the window, it was like midnight or something, I looked in the window and there he was sitting on the couch with a thousand blankets covering him. I turned away from the window and pressed my hand over my mouth to stop myself from making any sound. When I turned back I looked closer at his face. He was asleep. I wanted more than I wanted air to knock on the window and go in there and wake him up and hold onto him and feel that he was real and not just a ghost in my head but if he was asleep maybe it was because he had to be and I shouldn’t bother him so I bit the meaty part of my thumb hard to make myself not knock on the window. I went home and in the dark I went out to the woods and I started trying to get the pieces of our room back together. But I couldn’t see and I didn’t have any tools so I went home and lay in my bed buzzing in every part of my body like when I smoked pot but I’d smoked nothing except the sight of Jerome on the couch.

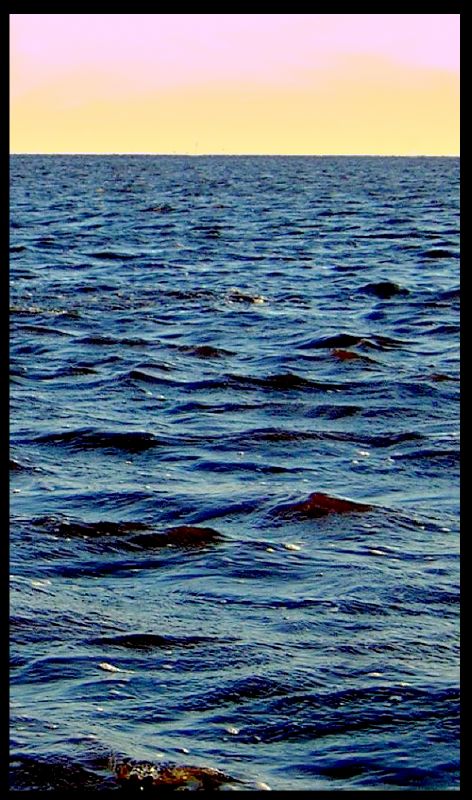

I skipped school the rest of the week and rebuilt our room. I knew Jerome wouldn’t be back in school just from what I’d seen when I saw him, no way was he ready to go back. Every night I’d go to his house at midnight. He started sleeping in his room again and I’d look in the window of his room and watch him sleep. One night it was warm enough that his window was open some and I could hear him breathing. I squatted under the window and listened to the sound of his breath, I could barely hear it. But it was the best sound I’d ever heard. I took the sound home with me and listened to it over and over in my head. Just that little whisper of sound.

In two weeks he was back at school for half-days. We didn’t have any of the same classes because he was in the smart track classes and I was in the for dumbasses classes but he was there. He left before lunch each day so we didn’t see each other but I knew he was there because I saw him coming in and I saw him leaving. I felt like I was stuck under water not talking to him but I didn’t know what was going on in his head and I felt sort of afraid of him. He’d really meant it when he tried to kill himself and maybe that meant we weren’t the kind of friends I thought we were, maybe he wasn’t happy being my friend. Maybe he knew I was thinking of him every time I jacked off and every time I hooked up with Mandy and every time I breathed. Maybe he knew I wanted more from him than friendship and that made him uncomfortable. Maybe he didn’t remember holding my hand and crying when he was almost all the way to dead or maybe he did remember it and it freaked him out and he hated me now.

He finally came back for full days. I still didn’t talk to him. He looked really tired all the time and I passed him in the hallway one day and got a good look at his arms. He’d really fucked them up. The scars were big and thick like purple ropes on his skin. The one on his left arm covered up the smaller scar he used to have from the glass. Nobody seemed to want to talk to him and he didn’t seem to want to talk to anybody. He had his head tilted down every time I saw him. His hair still hadn’t grown back, or his eyebrows. Maybe he was embarrassed about being bald. Maybe he thought it made him ugly. I thought it made him more beautiful than ever. His skin was so see-through sometimes I thought I could see his veins from twenty feet away in the crowded hallways. He looked like an angel to me.

And then one day after school he showed up at my house holding the skateboard I’d left in his sister’s car. He was breathing hard when I answered the door, like it had taken a lot of effort to walk across the state route into my neighborhood. “Hey,” he said. I just stood there looking at him. I could feel my body shaking with how hard I was trying not to grab onto him and crush him into me. He finally said “Can I come in?” and I was like oh yeah, and I let him in and we went back to my room.

He sat on the mattress on the floor trying to get his breath and asked for water and I went to get him some and I dropped the glass and it shattered in the sink. I threw it in the trash and got a plastic cup and filled it with water and brought it to him. My hands were shaking when I handed it to him. He took it and drank all of it and put the cup down and looked at me. I couldn’t meet his eyes. I felt naked. I couldn’t talk. “You’re bleeding,” he said and I still couldn’t look at him. “Look at your hand.”

I did. I guess I cut it on the glass I broke. I went into the bathroom and held my hand under the tap. I heard him come in behind me. He started rifling around in the medicine cabinet and found some hydrogen peroxide and a bandage. He sat me down on the toilet just like Joe had and bandaged my hand. I still couldn’t look at him. When he was finished he just squatted there in front of me looking at me. “What’s wrong, why won’t you look at me,” he said.

“I thought you were dead,” I mumbled, and then I started crying. He just looked at me for a minute and then he sort of put his arms around me and hugged me. It was awkward how we were sitting and I didn’t know what to do because if I put my arms around him too I knew I’d try to kiss him and I’d already lost him once and I knew if I did something stupid like that he’d know I was a sick faggot and he’d tell me to fuck off and he’d leave and I’d lose him again forever. So I didn’t do anything. I just wiped my face off and stood up and we went back in my room and he followed me and we started playing video games on the shitty black and white TV in there and eventually we started talking like everything was normal and the past half year had never happened.

Somehow it stayed like that for a while. It was like if we didn’t talk about anything that he’d gone through or that I’d gone through this school year it hadn’t happened. That day in the hospital when I’d held his hand and he’d cried had never happened. I’d never destroyed our room in the woods. He hadn’t gotten sick. It was easier to pretend that when he got well enough that we started skating again. I stuck to my board but he’d gotten hold of a pair of rollerblades somewhere and started tearing shit up on them; he was so fucking good at it. We built a half-pipe in the yard out of a bunch of shit Joe and me stole from the lumberyard. Jerome looked up all this shit about how to build them because I never would have figured it out. My dad had all the crap we needed for building because when he bothers to work he’s a construction worker. Jerome was never afraid of anything. The school year ended and we pretty much knew it was the last summer we’d have to fuck off all the time before we had to get jobs and we took advantage of it. He seemed a lot better than he had before he’d gotten sick. Sometimes he had to slow down from skating and use his inhaler and his asthma was a lot worse but he didn’t cut anymore. We both got in the local skating competition and I did okay but not great but he won the rollerblading division and got to go to State in July. All the time when we were hanging out it was like I put how I felt in a box on this shelf inside me and told myself I was never allowed to open the box when he was around. Ever. And I didn’t. He won the State championship too, that’s how fucking good he was. Joe drove us up there for it because he thought it was cool that Jerome was so good. Jerome’s parents didn’t know how good he was at skating and they probably wouldn’t have let him go but he just said he was staying the night with me and we went. I thought I’d die of joy when he won. He was going to go to nationals and be on TV and everything he was so fucking good and I was so glad for him. It was making him happy and making me less scared that one day he was going to try to kill himself again and make it this time.

He went on vacation with his family in August. While he gone all the feelings I had about him that I kept in that box, they wouldn’t stay in the box. I thought about him constantly. I slept out in our room in the woods thinking about him and woke up thinking about him and I started to realize that if I didn’t do something about how I felt that I wasn’t going to be able to keep hanging out with him every day. I was going to die of want, I was going to shrivel up and die of want being so close to him and never being able to touch him. I started hating myself hardcore because all along I’d been telling myself it was a fluke that I loved him and that I wasn’t gay but when he went on vacation I started thinking maybe I really was gay and that loving him made me gay because I loved him so hard and so deep. That’s what gay is, it’s when a guy loves another guy. I was so fucked. I turned it over and over in my head and kept telling myself I wasn’t gay because I’d hook up with Mandy sometimes and gay guys don’t hook up with girls. But I couldn’t believe it the way I wanted to believe it and I drank with my brothers every night to quit thinking about it but in bed dizzy and drunk I’d think about it anyway.

He came back and he seemed a little different. There were only two weeks till school started and he seemed different the way he skated. Like he wasn’t afraid of anything. For three nights I watched him in the halfpipe with my guts in knots thinking there was no way he was going to pull of the things he was doing. It was so hot outside then, we were always covered in sweat even late at night. On the third night I was practically crying while I watched him going through the routine he was building for the national competition. He was doing the craziest shit, he was doing things no one else did, not even on the competitions on TV. He was scaring me. It was dangerous, what he was doing. And he wouldn’t stop. He kept going until one in the morning and he only stopped then because he had an asthma attack and he’d left his inhaler at home and he just couldn’t keep skating. He slowed until he was rocking back and forth in the bottom of the halfpipe and then he lay flat on his back wheezing and whistling air in and out of his lungs and kind of holding his arms around himself and shaking and I wished I could give him the air in my own lungs. I went over to him and pulled his skates off his feet while he wheezed. He was starting to cry. Calm down calm down, I told him, you’re gonna panic and make it worse. Calm down, calm down. He started to, he started to calm down and his breath sounded a little better. It gradually evened out and then he just started crying again all of a sudden. I’m sorry, he kept saying. Shut up, it’s okay, I told him. You’re okay. I picked up his skates and pulled him up to his feet and we went inside into my room. Joe was gone somewhere and I hadn’t seen Marty in about three weeks so we had it to ourselves. Jerome was crying so hard I thought he was going to get sick. I dropped his skates on the floor and shut the door and sat him down on the bed. He backed up with his back against the wall and pulled his knees up and cried for a long time. I just kept my hand on his shoulder and couldn’t move I was so paralyzed with want. I leaned against the wall and just watched him cry. What is it, I finally asked him.

It’s everything, he said. I’m sorry.

I said, don’t be sorry, you have nothing to be sorry for.

He said, I fucked everything up when I got sick and I’m sorry and I should have told you sooner that I’m gay. It’s all right if you want me to fuck off out of your life, I’ll understand.

It got quiet in the room when he said that. He leaned his head against the wall and didn’t look at me for a minute. All the words I wanted to say were stuck in my throat like a bubble, pressing against my tongue so hard they hurt. He finally looked at me again. You’re gay too, he said.

No, I said. It wasn’t like I said the word no. It was like the word no just came from my lips all by itself.

Don’t lie, he said. He stared right at me and I could hear the high-pitched sound of my ears ringing while we sat there and his leaking blue eyes leaked right into my eyes. Then he kissed me. He leaned his face into me and I pushed my head as far back into the wall as it would go because if he was fucking with me it was going to crack me for sure. He put his mouth on mine and I stayed frozen for a split second before what was happening caught up with me and I kissed him back. His hands came up and brushed over my face, went down my back and wrapped around the back of my head and pulled me into him. I melted. I turned into oil and melted on him, the hidden box open and pouring out onto him and into his body. I don’t remember taking our clothes off, I just remember how he felt. And we were naked together on my bed and he was touching me and I was touching him and I felt like God was inside me. Jerome’s eyes were staring holes through me everywhere they touched me, the black of his pupils something I swam in the oil slick of our bodies naked and sweaty and touching. I didn’t know how to do this but it didn’t matter and all the little things in my brain that worked to make me know what I was doing stopped working so that I was fading in and out and it was only experience, the experience of touching Jerome after wanting to for so, so long, and it was different than I imagined it would be because no way did I think it could feel this good to touch him, to just raise my hand and touch his face, to see him tilt his head back with his eyes half closed and streaks of salt on his face from his dried up tears.

After some time I realized that I was inside him and that we were both making sounds and that the side of his face I could see looked like he was in some ecstasy and some horrible pain at the same time. I held still for a moment and he whispered don’t stop, don’t stop, and I kept going and it turned into experience again and nothing else in the world existed. Jerome started making these sounds and I put my hand over his mouth and he came and I came with my face buried in the back of his neck and our bodies touching everywhere they could touch at all and I couldn’t believe anything, it all felt like I was asleep and I was scared I was going to wake up and it would be back like it was. We hadn’t just fucked. Had we? But God, we had, because our bodies were still in a sweaty heap tangled together so tight that when I flexed my arm muscles his fingers moved.

We lay there like that forever. Our hands played together. The heat didn’t matter. Nothing mattered but that I was touching him and he was alive in this bed with me.

He fell asleep. I stayed awake, watching him, touching his arms, his chest, his face. After a while I realized someone else was awake in the house. I could hear someone moving around. My dad maybe. Or Tim. I started thinking what would happen if they came in here and saw us. I started thinking what would happen if anyone at school found out. If Karl found out. I started thinking what they’d do to us. I crawled out from under Jerome’s arms, unstuck the stickiness we stuck together by and put on a shirt and some jeans and went and took a shower. When I came back in the room Jerome was awake.

“Why’d you get up?” he asked.

“I just needed a shower.” I sat down on Joe’s mattress on the floor.

“What’s wrong?”

I shrugged. “Nothing.”

“That’s bullshit, something’s wrong. You didn’t like it.”

“I liked it,” I said. “I liked it more than anything I’ve ever liked.”

“Then what?”

“No one can find out.” I bit my hand. I hated this. I wanted to tell everyone. I wanted everyone to understand how beautiful this person was who was looking at me like I was tearing him up. I wanted everyone to know how much I loved him. But that couldn’t happen.

“Why?”

“I just—” I couldn’t explain to him. I couldn’t say, I’m not really gay, I just happen to love you and you happen to have a dick. And also if anyone knows about this they might try to hurt you and that can’t happen…

“You think you have something to lose,” he said flatly. I looked at him. “I don’t have anything to lose. I don’t care anymore who knows I’m gay. I don’t fucking care. The only thing I care about is winning at Nationals.” He looked up at the ceiling.

I felt a smear spreading under my skin. “What about me?” I said. “Don’t you care about me?”

He looked at me. “Yes.”

“Then just don’t tell anyone. That’s all.”

He looked back at the ceiling and shrugged. “If that’s what you want,” he said.

I crept back over to the side of the bed and reached out to touch his hand, afraid for a second that the feeling I had that everything had been a dream was a true feeling and none of the amazing things that had happened were real. But he took my hand and looked at me, looked through my eyes and out the back of my head and I knew it was real. I knew I was real again. I crawled into the bed next to him. He made room for me.

We laid like that until morning, him naked on the bed staring at the ceiling and me lying with my clothes on next to him, gripping his hand and seeing in his face that no matter how much I love him and how much I touch him, I’ll never get inside him all the way. No matter how much time we spend in our room in the woods he’ll still stay in the room inside his head. I could see it in his face. It will be like it’s always been. I’ll never get inside him. And the only way I’ll be able to handle it is if I lie to myself.

And so I swallow it and I lay next to him and the lying lies between us.