Ocean

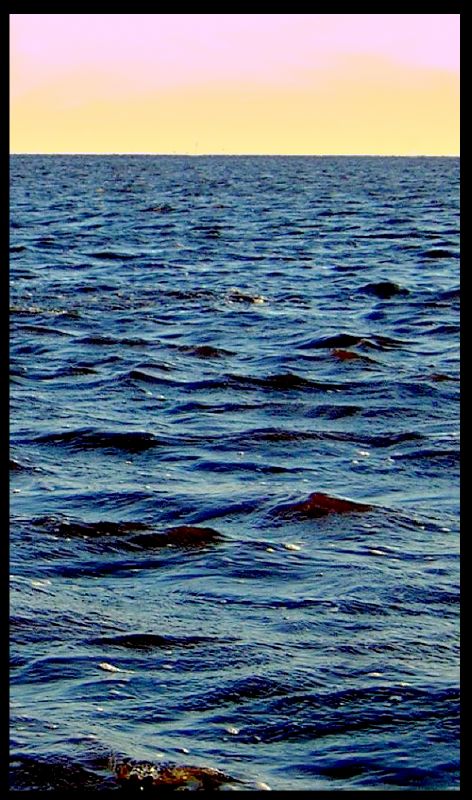

My brother is obsessed with the ocean. I don't think it's healthy. But, among the things that are unhealthy about him, it's the one that concerns me least.

My brother is obsessed with the ocean. I don't think it's healthy. But, among the things that are unhealthy about him, it's the one that concerns me least.Jerome is fifteen, four years younger than me. Some psychology majors have a specific reason why they chose the major they did, and they don’t discuss it. Jerome is my reason. He does things to himself that are not normal. There have been a lot of lies in my family and he seems to be the one who takes the punishment for the evilness of lies, though he isn’t the one who tells them. Others tell them, my uncle, my parents, I tell them. Jerome doesn’t lie. When he feels he can’t tell the truth, he says, “It’s a secret,” and that’s not a lie.

Today, on the edge of a saltwater marsh connected to open ocean, I catch a fish. My father and Jerome watch me reel it in. When my father nets it—thrilled, on his ideal vacation, netting an ocean fish his kid caught—Jerome can’t watch. He doesn’t eat animals. He became vegetarian when he was six, when his first-grade class took a field trip to a farm. He told me about it last year, when he was so sick we were sure he was going to die. When he told me he was lying back pale against a white pillow and held my hand in the darkness. He remembered so clearly, he said, and I thought at that moment, yes, we remember more intensely the moments of our lives when we experienced strong emotion, and I’ll remember this moment forever—he told me about a woman in a big dusty barn with sixty first-graders crowded around her. She pointed to parts on the body of a cow tethered inside the barn and explained what the parts were used for—hamburger, steak, soup bones, hot dogs. Jerome looked into the shining black eye of the cow and threw up on the straw floor of the barn. I was ten then. I remember the nightmares after his trip to the farm. When he woke in the night, he didn’t go downstairs to our parents’ room. He crawled under my bed and slept there.

Now, the fish I’ve caught flops on the sand, its shining gray eye looking up at my father and I looming over it, and Jerome turns with his hand on his stomach and walks away. My father wonders aloud whether to keep it and fry it for dinner or not; our hotel room has a stove, all we’d need to pick up at the store would be butter and maybe an onion. It is a medium-sized fish, and could feed two of us—my mother and father, because after seeing Jerome’s face, I know I won’t be able to eat it, no matter how appetizing it might smell while it cooked. I remove the hook from the mouth of the fish and toss it flopping and shining through the air back into the saltwater of the marsh. My father looks irritated; I’ve remained silent and decided the fate of the fish, ignoring his wishes. Jerome squats in the sawgrass at the water’s edge a hundred feet away. He still has his hand over his stomach and I wonder if he’ll get sick. But he doesn’t, and I continue to fish as I watch him. He stands after some time and walks around and I cast my line, hoping I won’t catch another, content enough just to have my feet in sticky seawater twelve hours’ drive from where we live in the Midwest.

In the evening, I go with our parents to a seafood restaurant; Jerome stays in the hotel room when we leave, as I’d known he would. Over a dinner of clam chowder and hush puppies and deliciously fried fish that I hadn’t had to look at flopping on the sand earlier, my father and I have our umpteenth argument about my choice of college majors. He’s always been so certain I’d study the sciences, watching through my childhood as I categorized nearly everything, tested ideas, kept notes about my experiments with the chemistry set he’d given me when I was eight. But psychology, to him, is not a science—never mind that I’ve been categorizing and studying and (even, secretly) taking notes on the psychoses of my younger brother since he was six and declared his vegetarianism at the dinner table, thus precipitating the tears then arguments and fights and eventual deadly silence that have become the hallmark of his relationship with my father. No, psychology is not a science; it falls, for my father, under the dreaded, fiercely democrat-leaning heading of “liberal arts,” despite my university labeling it a science. It’s an argument I can’t win, will never win. I only have it now to keep the conversation going and to fill the silence. In the back of my mind, I am thinking of Jerome and the cow and the fish. I’m sure that as soon as we’d gone from the hotel, he’d left the room and walked down to the beach to squat down on his heels with his arms wrapped around his legs and stare out at the water like he’s done nearly the entire time we’ve been on this vacation. If he isn’t staring out at the water, he’s in it. It holds some power over him, the nature of which I can only hypothesize.

I know he is synesthetic. I know it from his drawings. Among other things he does freakishly well, my brother is expert at rendering images of what he sees, and also of what he sees that no one else can see. I gave him an expensive pastel set for his birthday when he was ten. My father was furious; he hates that Jerome is artistic, says art is a foolish pursuit, certainly not fit for the son whose stint in Boy Scouts had lasted less than three meetings. In retaliation, it seemed, even though the gift had been bought before he could have known what I planned to give Jerome, he gave Jerome a Swiss army knife—one with all the bells and whistles, magnifying glass, corkscrew, screwdriver, twenty different blades, the one that weighed nearly more than Jerome did when he was ten and skinny and small. Jerome used my pastels to draw, and the knife from my father to cut himself. Which was the worse gift, I wanted to know. From time to time, in the pictures Jerome drew, the colors were warped. He drew my mother’s cutting board with a loaf of French bread on it, and the whole picture, on the gray paper I’d also given him, had a blue tinge to it that I knew he saw and was drawing as he saw it, and was not a mistake. He drew a portrait of me and I had a pink halo. I asked him about it. He said I was pink. I told him I wasn’t, was the same color as him, had the same dark brown hair—this conversation occurred before chemo and radiation left him bald as an egg—and that our skin tones matched nearly exactly. I couldn’t argue with him, because he knew he was right, so I formed a hypothesis that he was colorblind—which, we learned in science class, didn’t necessarily mean a person saw in tones of black and white and gray, but rather confused certain colors, or was unable to see the difference between blue and purple or between red and green or other combinations. To test this hypothesis, I checked out some books from the school library and had Jerome look at circles of blue dots with numerals spelled out in yellow dots inside them, had him tell me the difference between red triangles and green ones, and on and on—he passed every test in the book, and therefore wasn’t colorblind. What is it then, I asked him—and he told me it was a secret, that there was no answer. In the case of other beings four years younger than me, I would have chalked that up to mean they didn’t know and didn’t want to let on that they didn’t know; in Jerome’s case, it meant he knew and was uncomfortable telling me. I returned to the library and asked for help in locating an answer to my question: Why would someone who was not colorblind see colors in different ways from everyone else? I learned about synesthesia in this way, and it became obvious to me that this was Jerome’s reason for drawing things in odd colors; he literally saw colors associated with his emotions. It also explained why he tended at times to describe sensation or memory in terms of color. If I asked him how his day was when he returned from school, more often than not he’d answer with a color: blue, most frequently, although sometimes orange (which I came to learn meant he felt sick), or yellow (some sort of Jerome-specific hybrid of guilt and anger) or rarely, pink—pink, the color of me, of not-badness. How lucky for me, to be a cast in a color that to my brother means the absence of pain.

I know he is synesthetic. I know it from his drawings. Among other things he does freakishly well, my brother is expert at rendering images of what he sees, and also of what he sees that no one else can see. I gave him an expensive pastel set for his birthday when he was ten. My father was furious; he hates that Jerome is artistic, says art is a foolish pursuit, certainly not fit for the son whose stint in Boy Scouts had lasted less than three meetings. In retaliation, it seemed, even though the gift had been bought before he could have known what I planned to give Jerome, he gave Jerome a Swiss army knife—one with all the bells and whistles, magnifying glass, corkscrew, screwdriver, twenty different blades, the one that weighed nearly more than Jerome did when he was ten and skinny and small. Jerome used my pastels to draw, and the knife from my father to cut himself. Which was the worse gift, I wanted to know. From time to time, in the pictures Jerome drew, the colors were warped. He drew my mother’s cutting board with a loaf of French bread on it, and the whole picture, on the gray paper I’d also given him, had a blue tinge to it that I knew he saw and was drawing as he saw it, and was not a mistake. He drew a portrait of me and I had a pink halo. I asked him about it. He said I was pink. I told him I wasn’t, was the same color as him, had the same dark brown hair—this conversation occurred before chemo and radiation left him bald as an egg—and that our skin tones matched nearly exactly. I couldn’t argue with him, because he knew he was right, so I formed a hypothesis that he was colorblind—which, we learned in science class, didn’t necessarily mean a person saw in tones of black and white and gray, but rather confused certain colors, or was unable to see the difference between blue and purple or between red and green or other combinations. To test this hypothesis, I checked out some books from the school library and had Jerome look at circles of blue dots with numerals spelled out in yellow dots inside them, had him tell me the difference between red triangles and green ones, and on and on—he passed every test in the book, and therefore wasn’t colorblind. What is it then, I asked him—and he told me it was a secret, that there was no answer. In the case of other beings four years younger than me, I would have chalked that up to mean they didn’t know and didn’t want to let on that they didn’t know; in Jerome’s case, it meant he knew and was uncomfortable telling me. I returned to the library and asked for help in locating an answer to my question: Why would someone who was not colorblind see colors in different ways from everyone else? I learned about synesthesia in this way, and it became obvious to me that this was Jerome’s reason for drawing things in odd colors; he literally saw colors associated with his emotions. It also explained why he tended at times to describe sensation or memory in terms of color. If I asked him how his day was when he returned from school, more often than not he’d answer with a color: blue, most frequently, although sometimes orange (which I came to learn meant he felt sick), or yellow (some sort of Jerome-specific hybrid of guilt and anger) or rarely, pink—pink, the color of me, of not-badness. How lucky for me, to be a cast in a color that to my brother means the absence of pain.We finish our seafood extravaganza and drive back to the hotel in silence, my father picking his teeth with a mint-flavored toothpick and my mother staring wordlessly out the passenger window. She has spoken dramatically less frequently since a certain point in my brother’s illness last year. The point was just as we were certain he wouldn’t live. He was home then, after a second round of chemotherapy had failed to kill the leukemia in his marrow. He almost always stayed in bed, too weak to get out for anything more strenuous than a trip to the bathroom. I spent a lot of time at his bedside reading to him. He loved fairy tales and we kept a book of them between his mattress and box springs; though Jerome was practically on his deathbed, my father would have flown into a rage to know that this son of his had a fondness for stories in which princesses were rescued from dreadful witchy-spells by handsome knights on flawless white steeds. One night during this time, a screaming argument woke me. It was ten thirtyand I was in bed nearly asleep; high school started at such a ridiculously early hour. The hysterics outside my door were my mother’s. It isn’t true, it’s a lie, it’s a lie, she repeated over and over. My father’s cracked and raw anger cut through her voice. I sat upright in bed and immediately went to the door and opened it. My father turned to me from Jerome’s doorway, his face an angry purple-red, much more vivid than my mother’s white-lipped hysterics. This doesn’t concern you, he snapped at me, and walked forward to shove me back in my room and slam my door. Before he was able to do so, I caught a glimpse of Jerome through the space between my father’s raised arm and his body. Jerome’s eyes were closed and I thought I could see reflections of light on his face—tears, from my brother who I hadn’t seen cry since he was six. The door closed on me and I was plunged into blackness and fear. I went back to my bed and heard my parents out in the hallway, I heard them close Jerome’s door as well and go down the stairs to their own bedroom. The silence filled my head, my ears rang so loudly with it that my eyes watered. I wanted badly to open my door and enter the sticky-sweet smell of sickness in Jerome’s room, to suck out all the fear and pain I knew he was feeling, to find out what had set off this wretched state of affairs, but I stayed in my own darkness because I knew Jerome wouldn’t, or couldn’t, talk to me; I knew he would whisper “it’s a secret” as he did whenever I most wanted an answer from him to explain some action he’d taken, some answer to a question that didn’t make sense. He wouldn’t talk to me, he would close his eyes, he would whisper “it’s a secret…”

I laid back down on my bed and tried and failed to simultaneously count my breaths and my heartbeats—it was impossible, their rhythms both rushing but too different—and then I heard a choking cry that I knew came from my mother’s throat, and a thump, and I left my bed and walked out the door counting my steps to keep myself from cracking with fear. My mother was slumped in the doorway of Jerome’s bedroom. I stood looking at her at my feet, unable to make myself look into the room to see what had reduced her to the huddled mass on the floor, her voice cracking around non-words and her fingers digging into her crossed arms. To make myself look up to see the cause of this, I had to lift my hands to my head and push my chin up and still my eyes wouldn’t go—further I pushed up my chin until my eyes in looking down couldn’t see my mother, could see instead the sight of Jerome naked and spread-eagled on his bed covered in blood. I heard my breath suck in and my father appeared, said Oh my God, and picked up the phone on Jerome's desk and called an ambulance. The room began to fade at the edges and I felt a tightness in my chest before my breathing resumed by itself. I took five steps over to my brother. One of them was over my unconscious mother. I counted them as I had been trying to count my breaths and heartbeats. His shirt was in a crumpled heap on the floor. I watched my hand snatch it up and fling it over his bald nakedness, I watched my hands without knowing how to stop them uncurl Jerome’s fingers from around the piece of broken model-train track he’d used to cut his wrists open in horrible, gaping meaty gashes. My fingers were sticky with his blood and I wiped them on my shirt. His sweet, sticky blood—his red blood cells, swimming unprotected by white blood cells all over his forearms, his naked belly, his bed sheets. He still breathed. I could hear it over my father's panicked voice screaming at the switchboard operator. It was shallow and barely visible, but he still breathed. I sat on the edge of the bed and flipped a piece of the sheet over his wrist. Direct pressure, I thought. Direct pressure can stop the bleeding. I pressed down, hard, crushing his fragile wrist into the bed. The bed was too soft. I picked up his limp hand and laid it across my thigh, his fingers curling around nothing as I pressed hard against the faintly pumping flow of blood. My father seemed to have conveyed the urgency of the situation to the operator; he hung up the phone and followed my lead and pressed the other wrist. We didn’t speak. Will he live? I asked my father over and over in my head, but he couldn’t hear me and didn’t answer. My mother remained on the floor. The ambulance arrived after an interminable amount of ear-ringing time in which Jerome’s breath grew more and more shallow and I could see less and less, only the darkening sheet I had pressed over his pale skin. Tend to your mother, my father said, and picked Jerome up as though he were a rag doll, his head flopping limply against my father’s arm, carried him out the front door to the paramedics. He’ll die, I thought, sitting there dumbly holding the soaked sheet. He is too sick and too empty of blood and he will die. I could have stopped this. I could have come in here after the argument and I could have stopped this. But I didn’t. I didn’t come in because I thought I knew what I would find, what he would say. My mother groaned on the floor. I couldn’t move.

Since that day, my mother hardly speaks. She speaks only when she feels she needs to. Which is not as often as I feel she needs to. Remember me? I ask her in my head, but like my father that night, she doesn’t hear me and can’t answer. Now she sits in the passenger seat as my father drives along a strip of road between restaurants and hotels along the Atlantic coast, not speaking. The only way to fill the silence is to converse with my father, and I feel I’ve had enough of that for one night. And so I pass the time in the car by counting the signs, counting the people we pass, counting the traffic lights and potholes and palm trees.

When we get back to the hotel, my parents decide that they’ll have a bottle of wine and sit out on the balcony for a while. I leave them to it and kick off my shoes in the entryway, pick up a hooded sweatshirt and walk down to the beach. It looks like it might rain soon; the wind has picked up and the sky is filled with gray clouds, the same blue-gray as the water but lighter, because the sun is behind them and the only thing behind the water in the sea is the ocean floor, dark as midnight. I wonder which direction Jerome has wandered and see the pier lights coming on to the north; I choose that way to walk.

It’s not long before I find him. He’s maybe half a mile up the beach, sitting just out of the tide on the sand, his knees up and his arms around them, his black shirt dark against his pale skin. I sit down next to him on the sand without speaking. He moves closer to me and I give him the sweatshirt. “Thank you,” he murmurs and puts it on. I look at the scars on his arms while he pulls it over his head. When he’s cold, they become purple. He’s almost always cold now since he went into remission. Before, he was almost always hot.

“What are we doing tomorrow?” he asks after a while.

“I don’t know,” I answer. “Dad said something about going to a lighthouse. Do you want to go?”

“Yes.”

“I wonder if it’s one we can go inside. Like the one two years ago. Remember?"

He nods. Two years ago, our vacation had been to the rocky coast of Maine. The lighthouse was small and the view so wide I thought Jerome was going to go over the railing at the top trying to suck it all in.

“It might rain,” I say, looking up at the sky.

“I know.”

“Why didn’t you bring a rain jacket?”

“I won’t melt. Why didn’t you?"

I fill my hand with cool sand and let it trickle down my palm to make a tiny sandcastle. Jerome is rocking back and forth on his heels. Abruptly he stands and says, “I have to walk. Do you want the sweatshirt back?”

“Keep it,” I say, and watch him walk away. He folds his arms over his chest and hugs his body while he walks away from our hotel and toward the pier. I don’t follow him. I stay on the sand, looking out at the water and trying to feel the feeling he feels when he looks at it, even though I have to bend my brain hard to imagine I can understand it.

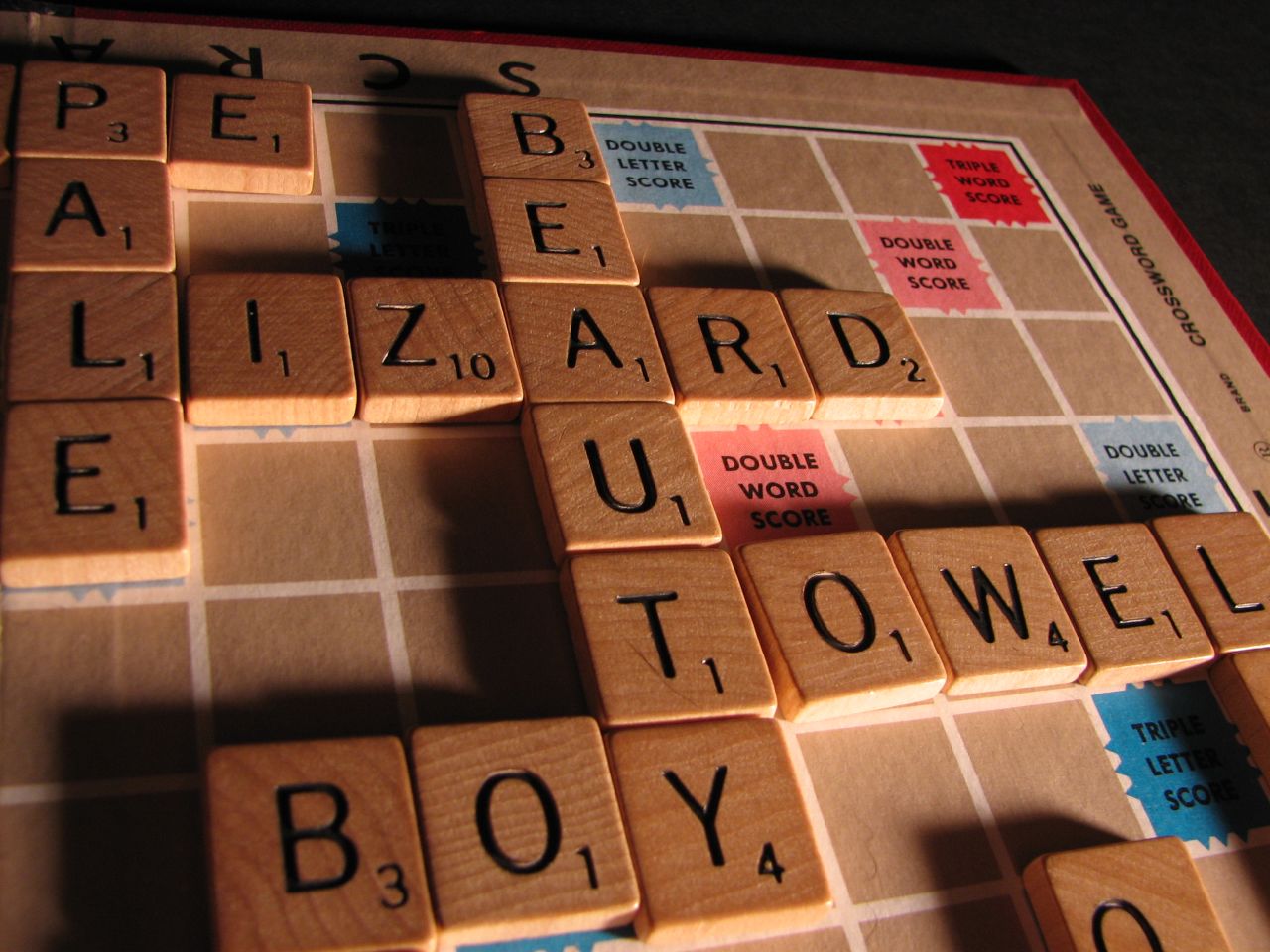

The next day it’s drizzling in the morning, and our parents decide to forgo the lighthouse. They want to go shopping and to a restaurant further away than the one we drove to last night. Jerome and I don’t want to go and so they leave after breakfast, saying they’ll be back early afternoon. Jerome and I get out our Scrabble board and set it up on the floor in front of the sliding glass door that leads out to the balcony. We open the door to let in the sound of the waves. He draws a letter: C. I draw an H. He goes first and spells out MOTOR on the pink star at the board’s center. I study my letters and create AFRAID, pleased with myself to have used five letters in one turn. “I’m afraid,” Jerome says tonelessly after I tally our scores on a notepad.

“What are you afraid of?” I ask as his eyes move over the letters in front of him, trying to find an arrangement of them that will make a word. He spells out TOUCH. I wish I had a W and a Y so I could spell out my question, but I don’t, so I have to ask it aloud. “Why?” He doesn’t answer and I create FARMS, which is lame.

“I met someone,” he finally says, rearranging his letters with one hand and pressing hard on his stomach with the other. Outside, I can hear the water washing up onto the beach, and I know Jerome is listening to it as well with at least part of his consciousness. He writes BOY. There’s the Y I needed, I think, before realizing he’s telling me he’s met a boy. I have several Es and ask, HERE?

“I met someone,” he finally says, rearranging his letters with one hand and pressing hard on his stomach with the other. Outside, I can hear the water washing up onto the beach, and I know Jerome is listening to it as well with at least part of his consciousness. He writes BOY. There’s the Y I needed, I think, before realizing he’s telling me he’s met a boy. I have several Es and ask, HERE?He nods. I write our scores. “Last night?” I ask aloud.

He nods again, pressing his knuckles into his teeth and biting them. Jerome told me last year, back when he was dying, that he knew he was gay. But as far as I knew, he had not so far met someone. He writes DEER.

“Tell me about him,” I say.

He drops his hand from his mouth. “His name is David. He’s sixteen. He has dark hair and I don’t know what he looks like in the daylight. We swam together last night. In the dark. And then he laughed and he left.”

I let the silence hold for a few moments as I move my letters around, searching for a word. Finally, I use the Y in BOY to write BEAUTY. The B falls on a double word score; it’s worth a lot of points.

“Why are you afraid?” I ask.

He opens and closes his hands several times, looking at them. “Sometimes, I see a place in front of me, any place, a parking lot or the outside of a hospital or a highway or the ocean, any place. I see a place in front of me and the light is just so. Just a certain way. And I feel every feeling at once. I can hear the sound of what I see and I can also smell the taste of it and see the color of the feeling of it. I feel everything anyone has ever felt. It—” he pauses and writes LIZARD, outdoing my points for BEAUTY. “I was stung by a jellyfish last night in the water. Here.” He holds out his scarred arm and indicates a patch of redness near his elbow. “Everything turned blue. David touched my hand under the water. I thought it was an accident. But it wasn’t. I touched his hand too, we touched our hands together. I could see the lights of the hotels reflecting in the water through the blueness and I tasted the taste that goes in David’s veins when he’s asleep and saw the inside of his room with his schoolwork and a dark green blanket on his bed and some stupid school pendant up on the wall and the way the skin of his back looks when he’s stripping to put on sweatpants for bed. I saw all of that while we were swimming in the dark touching our hands together.” He pauses, drawing letters from the bag to replace the ones he’s used. “Then he told me to hold my breath. He pulled me under the water and he put our bodies together. He twisted us together. He tried to get inside my skin. I thought I should let him. Our chins and necks got locked on each other’s shoulders and our chests were pressed together. I thought I was drowning. I thought I could handle that. I thought the moment I let go and sucked the saltwater into my mouth would be a bad moment but after that it wouldn’t be so bad. But then he let me go. And he went to the surface and I followed him to it. He was swimming away laughing. What does that mean?”

He opens and closes his hands several times, looking at them. “Sometimes, I see a place in front of me, any place, a parking lot or the outside of a hospital or a highway or the ocean, any place. I see a place in front of me and the light is just so. Just a certain way. And I feel every feeling at once. I can hear the sound of what I see and I can also smell the taste of it and see the color of the feeling of it. I feel everything anyone has ever felt. It—” he pauses and writes LIZARD, outdoing my points for BEAUTY. “I was stung by a jellyfish last night in the water. Here.” He holds out his scarred arm and indicates a patch of redness near his elbow. “Everything turned blue. David touched my hand under the water. I thought it was an accident. But it wasn’t. I touched his hand too, we touched our hands together. I could see the lights of the hotels reflecting in the water through the blueness and I tasted the taste that goes in David’s veins when he’s asleep and saw the inside of his room with his schoolwork and a dark green blanket on his bed and some stupid school pendant up on the wall and the way the skin of his back looks when he’s stripping to put on sweatpants for bed. I saw all of that while we were swimming in the dark touching our hands together.” He pauses, drawing letters from the bag to replace the ones he’s used. “Then he told me to hold my breath. He pulled me under the water and he put our bodies together. He twisted us together. He tried to get inside my skin. I thought I should let him. Our chins and necks got locked on each other’s shoulders and our chests were pressed together. I thought I was drowning. I thought I could handle that. I thought the moment I let go and sucked the saltwater into my mouth would be a bad moment but after that it wouldn’t be so bad. But then he let me go. And he went to the surface and I followed him to it. He was swimming away laughing. What does that mean?”Jerome turns his eyes on me full force, which he rarely does. He seems to know that eyes like his hold some sort of power over the rest of us mortals. Even without eyebrows and eyelashes to set them off his eyes are still beams of blue so blue they’re nearly purple, and they change color with his mood and comfort level. They literally seem to cut into whatever it is they look at. He puts these X-ray eyes, these CAT scan eyes, these radiation eyes right into mine and asks me what it means that David did what he did.

I can’t answer. I wish I had an extra R; then I could spell how SORRY I was to not be able to help him. I drop my eyes from his and stare at my letters. “Maybe he wanted you to follow him,” I answer.

“No,” Jerome says. “I watched him run up the beach once he got out of the water. He was running away.”

“He’s afraid too, then,” I answer.

“He laughed like he knew he has power over me.”

I turned that over in my head while I write FLOW. How many fifteen-year-old boys could communicate like Jerome? Could say what they thought about someone else having power over them? Few. Very few. How many nineteen-year-olds, though, could there be to have a brother like this, who had been cutting himself since he was ten, who could draw anything, whose senses were all tangled and mixed so that he saw what he heard and felt what he tasted, who had beaten leukemia and come so close to killing himself and who could cut through anything he looked at with his laser-powered iris-colored irises? Am I lucky to have this brother? Am I lucky it was Jerome instead of me our uncle chose to be his victim? If I could, would I take it so that Jerome might be spared?

I can’t answer these questions right now or ever and feel myself mirroring what my brother does when he’s uncomfortable or afraid: I draw my knees up to my chest and wrap my arms around them. Jerome watches me for a moment and then writes REFLECTS, using all seven of his letters and effectively winning the game early, since I’ll never be able to stage a point comeback after that. “You’re afraid too,” he says, not looking at me.

“Some,” I say.

You can hide nothing from Jerome.

Our parents return in the afternoon. The drizzle has continued all day and in the early evening it finally lets up. Though our hotel room has a fridge and the stove, our parents seem to want to eat at a restaurant for every single meal, and though they’ve had lunch out already, they want to go out again for dinner. There’s nothing to eat in our room except a bag of pretzels and some peanut butter, so I go with them, but Jerome says he isn’t hungry (and I can see this by looking at him, dark circles under his eyes, he’s had his hand over his stomach all day like he did sometimes during chemo) and stays on the couch wrapped in a blanket looking out the sliding glass door at the water.

I feel like crying in the car with my mother and father. The sky is still gray and I’m scared for my brother. He ate nothing all day while I was with him and I doubt he’ll suddenly decide he’s hungry and eat the bag of pretzels while we’re gone. He’s too thin. He doesn’t seem to notice his body; when he’s sick or injured (and his injuries are so frequent that it’s impossible for them to all be accidents), his eyes get a slight glaze over them and he carries on as if nothing is wrong. He goes to school even if he has a fever and is throwing up; when I asked him, he says he just excuses himself and runs to the bathroom if he has to throw up while he’s in class. Two years ago, before he got sick, he and I went camping in the mountains and he broke his wrist. I didn’t know about it until the next day when he asked if I could drop him off at the hospital on the way home. He’d managed to hide it from me and to hike and climb as if nothing had happened. We didn’t know he was as sick as he was when he first got leukemia until he passed out in the cafeteria at his school and the school called my mother to ask which hospital she wanted them to bring him to—a question she’d been asked before and by then could somewhat handle.

I barely eat at dinner. My father talks on and on about some golf course he’s going to go to tomorrow. I don’t tell him that I watched the weather report and it’s supposed to storm all day tomorrow. I hate him so much sometimes for what he did to Jerome that I hope he’ll swing his metal club up and be struck down by the lightning hand of God. The bastard. I hate him so much more when something is wrong with Jerome. The rest of the time, I can stand him enough, because I can make myself not think about it.

When we return to the hotel Jerome is in the bathroom; I can hear the shower running. Our parents decide to walk off the indulgent dinner they’ve just eaten and they leave for the beach. I wait out on the balcony for Jerome to finish his shower. When he does, he joins me. He’s dressed in black again. He sits on the edge of a plastic chair with his bare feet up on the railing. His eyes are red and faintly glazed over. “Are you sick?” I ask him.

When we return to the hotel Jerome is in the bathroom; I can hear the shower running. Our parents decide to walk off the indulgent dinner they’ve just eaten and they leave for the beach. I wait out on the balcony for Jerome to finish his shower. When he does, he joins me. He’s dressed in black again. He sits on the edge of a plastic chair with his bare feet up on the railing. His eyes are red and faintly glazed over. “Are you sick?” I ask him. He shrugs. This means yes. I bite my lip.

When Jerome was nine, he threw up so much that he became malnourished. My father could not beat any sense into him, my mother could not shake any sense into him. I knew something bad was happening to him, but I would never let myself think about what it might be, because I knew it could easily have been me. It could have been me going to Uncle Stan’s. Jerome threw up so much he began to throw up blood. Our pediatrician could find no reason for Jerome to be so sick so constantly; rounds of blood tests were performed, scans of his major organs were done. When threatened with medical tests Jerome could hold it together and not get sick for about a week at a time, but his mental state would crumble rapidly when he wasn’t letting himself throw up. He lost it one day at school at Randy, a boy with whom he’d had some trouble in the past. Randy hit him on the back of the head at recess and Jerome snapped, punching Randy in the throat and downing him and then picking up a chair and smashing it over his body until the screams carried to the teacher who pulled Jerome away. My father beat Jerome with the buckle end of a belt. My mother, at the behest of Jerome’s school, signed him up for counseling. My parents handled my brother like some rabid animal; he was so dysfunctional that they had no idea how to deal with him other than to keep him as emotionally far from themselves as they could manage. He’d earn A’s on half his tests and F’s on the other half, not patterned by subject but by his state of mind. He had no friends and talked to himself and regularly woke screaming in the middle of the night, smashing his head repeatedly into the wall seeking unconsciousness. I could not believe how blind they were; once during a beating I tried to intervene, could not stand to see the lash marks on Jerome’s legs through his half-open bedroom door and I flew in and jumped on my father’s back, screamed “Stop taking him to Uncle Stan’s!” before my father whirled on me and said “What did you say?” in a tone of voice more deadly than I’d ever heard him use before. I backed out of the room and hated myself for my cowardice. I still hate myself for it.

The counselor my mother took Jerome to seemed like a nice man; we all had to meet with him for a family session before he started Jerome’s individual therapy. I became intrigued by this man’s profession; here was a person who was paid to extract people’s secrets, and to help them recover from the damage done by keeping them. I wanted to know everything each time Jerome came home from a session there. Jerome told me about Doctor Nathan. It was clear my brother was falling in love, at the age of nine, with his male therapist, and through this, I began to fall in love with him too. Did you tell your secrets yet? I’d ask Jerome after each session. Not yet, he’d tell me. I never will. I asked him why. He didn’t answer.

On the balcony we remain quiet, watching the water, and I remember: One Tuesday night he went to Stan’s for babysitting and I went to a friend’s house. I arrived back at home in the evening before Jerome, and when he came home in the back of my mother’s car, I knew something was even more wrong than usual. Jerome looked broken. His expression was flat, his eyes dead. His limbs seemed to operate under some other command than his own. I could not believe my mother didn’t see this. Jerome gathered his things from the back of the car and went into his room. When our parents had gone to bed, I snuck out of my room and into Jerome’s. He was lying on his bed with his eyes open, not moving. I crawled into his bed with him, tried to hold him. What happened, I asked him. He ignored me. I held onto him all night, dozing from time to time but always waking to see him lying in my arms with his eyes open, staring at nothing. In the morning we had to dress and go to school. I didn’t want to let him go; I was afraid. I knew he had an appointment that evening with Doctor Nathan. I hoped all day, distracted from school, that he’d help Jerome through this, because I felt so powerless.

Jerome didn’t come home from Doctor Nathan’s that night. My mother received a phone call in the kitchen while I was doing my homework. I saw her face do a sort of lurching motion and then she said “yes” and named a hospital and hung up the phone. She stood staring at it for a moment and I said “What happened?” and she said in a monotone, “Jerome kicked through the window in Doctor Nathan’s office and intentionally cut his arm with a piece of glass. He’s throwing up blood. They wanted to know which hospital to take him to.”

At first, I couldn’t believe she’d spilled this information. My parents were very hush-hush on the topic of Jerome when I asked, as if they knew they were doing something dreadfully wrong with him. Then I realized what she’d said. “I’m coming with you,” I told her. She nodded numbly and she and I rode in silence as my father drove, quaking with rage and muttering about how he was going to wring Jerome’s fucking neck and make him pay for the window. It was at this point that I realized the depth of my father’s contempt for Jerome, and knew I could never understand it and I never wanted to.

In the hospital, Jerome was sedated and lying back against white blankets. His arm was on top of the bedsheets, bound in gauze from his wrist to his elbow. A heart monitor beeped nearby. He looked tiny. His face was a deathly white against the darkness of his hair. My father stood looking down at him and then left the room. My mother and I held hands and watched him sleep. I had the sense that my mother wanted to speak but she said nothing. After some time she went out to join my father. I stayed in the room, held the hand of Jerome’s non-injured arm. Ages passed. He stirred and opened his eyes. “Blue,” he whispered, and looked at me, and his eyes glazed and he closed them. I felt tears on my face.

Now, on the balcony of a hotel in the Carolinas in the torpidity of August, his eyes have this same glaze and there’s nothing I can do to peel it away. “Let’s walk,” I say.

He nods and we go down to the beach. “Which way did they go?” he asks, and I know he’s referring to our parents. I’d seen them walking south while I sat on the balcony and gestured in that direction. He turned north, toward the pier. We walk for a while without speaking. Jerome walks so that the waves wash high on his legs, soaking his black shorts. He stops now and again to look out at the water and I stop as well, watching his back as his eyes suck up the sea. He draws his breath sharply in at one point and when he walks further up on the sand I ask if he’s all right. “I stepped on something sharp,” he says, and he is limping slightly.

He nods and we go down to the beach. “Which way did they go?” he asks, and I know he’s referring to our parents. I’d seen them walking south while I sat on the balcony and gestured in that direction. He turned north, toward the pier. We walk for a while without speaking. Jerome walks so that the waves wash high on his legs, soaking his black shorts. He stops now and again to look out at the water and I stop as well, watching his back as his eyes suck up the sea. He draws his breath sharply in at one point and when he walks further up on the sand I ask if he’s all right. “I stepped on something sharp,” he says, and he is limping slightly.“Should we stop and see if you’re bleeding?” I ask him.

“No, it’s fine,” and we keep walking.

After a while someone falls into step with us. “David,” I hear Jerome say, and I turn to look, hungry to see this person Jerome is afraid of because he has power over Jerome. David introduces himself. He’s Jerome’s height, five ten or so, has dark hair as Jerome described—and is indescribably gorgeous. Leave it to Jerome to fall in lust with someone like this.

David walks with us to the pier. I leave some space between myself and the two of them, trying to let them have some sort of privacy, although I itch to hear what they’re saying to one another. There’s a bait and tackle and souvenir shop on the pier and I enter it and watch them walk out to the end of the pier. It’s nighttime by now. I buy a couple cheap postcards and some candy, walk the length of pier to where the two of them are sitting on a bench that faces the water, so close they’re nearly touching—and I see, briefly, that their hands are together under the railing of the pier. They snatch their hands apart when I approach. “I’m going to walk back, I’m a little cold,” I tell Jerome. He nods. I smile at the two of them, looking David full in the face and thinking, you hurt him and I’ll fucking kill you dead.

I walk back alone. I am afraid. I want something to go right for Jerome but know that it so seldom does.

Jerome is gone for a long time. When I go back up to the room, our parents have returned and are getting ready for bed. I drink a glass of water and return to the beach, sitting under a palm tree on a towel, hidden in the shadows. I wrap the sweatshirt around my shoulders and smell the salt on the air, waiting for him to come back and idly wondering when I’ll find out which classes I’ve gotten into for next semester. People walk by but more infrequently as the night goes on. Soon it’s been quite some time since anyone has walked by, and I don’t know what time it is. Two figures appear down the beach, in the direction of the pier, walking this way. I stay beneath the palm tree. They come closer and I can tell it’s Jerome and David. They reach the boardwalk of our hotel, not twenty feet from me, and I can hear them talking but can’t discern the words. David pulls Jerome close to him, and Jerome pulls away. I start up from my spot, ready to defend my brother, but the two of them are hurrying away, through the pool area and toward the parking garage. I sit back down and wait. I don’t think my brother has ever had willing sexual contact with another person before. I don’t know how he’ll handle it if something goes wrong. I don’t think he’ll want to talk to me about it if something goes right. I don’t want him hurt. I don’t want him hurt.

Jerome is gone for a long time. When I go back up to the room, our parents have returned and are getting ready for bed. I drink a glass of water and return to the beach, sitting under a palm tree on a towel, hidden in the shadows. I wrap the sweatshirt around my shoulders and smell the salt on the air, waiting for him to come back and idly wondering when I’ll find out which classes I’ve gotten into for next semester. People walk by but more infrequently as the night goes on. Soon it’s been quite some time since anyone has walked by, and I don’t know what time it is. Two figures appear down the beach, in the direction of the pier, walking this way. I stay beneath the palm tree. They come closer and I can tell it’s Jerome and David. They reach the boardwalk of our hotel, not twenty feet from me, and I can hear them talking but can’t discern the words. David pulls Jerome close to him, and Jerome pulls away. I start up from my spot, ready to defend my brother, but the two of them are hurrying away, through the pool area and toward the parking garage. I sit back down and wait. I don’t think my brother has ever had willing sexual contact with another person before. I don’t know how he’ll handle it if something goes wrong. I don’t think he’ll want to talk to me about it if something goes right. I don’t want him hurt. I don’t want him hurt.But I think he is. I hear a pounding sound and turn to see David running away, running back up the beach, and Jerome emerges and walks past me out to the water, and he doesn’t stop at the edge. He walks right out into it, still wearing all his clothes, until it’s swallowing him up, the whiteness of his skin getting lost in the pounding white of hotel lights reflecting on waves. My breath catches and I stand up, drop the towel, peel off the sweatshirt and kick off my shoes and go in after him.

The water seems colder at night. Jerome, I shout, but it’s drowned out by a wave, and I wait a split second before calling him again in the silence after a wave. I can see the back of his head moving away from me, getting farther and farther—he could always outswim me, even when we were small. I kick against the cold current, trying to reach him, watching him swim out into the belly of the night, his skin swallowed by the cresting waves between us.